01/02/2021

Military coup in Myanmar a severe setback for democratic and economic development

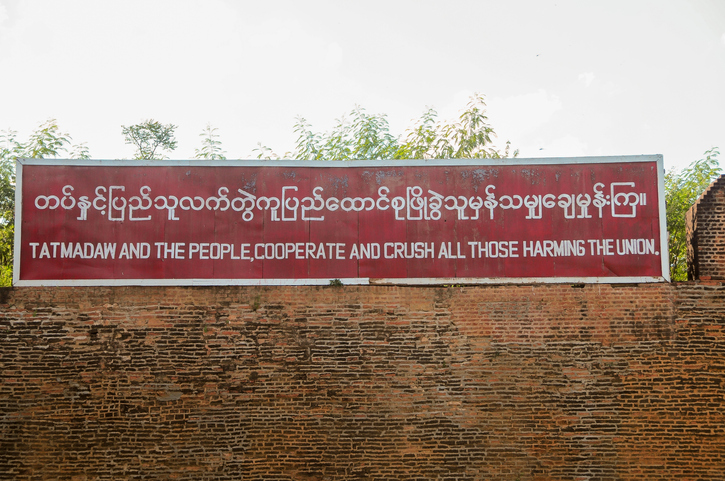

The Myanmar military (known as the Tatmadaw) seized power on 1 February in a coup d’etat. Military leaders announced the Tatmadaw would govern the country for 12 months under a state of emergency. The coup follows parliamentary elections in November 2020 which delivered a landslide win for the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The Tatmadaw claims the elections were marred by irregularities and that the NLD victory was therefore invalid. Suu Kyi has called on NLD supporters to take to the streets to protest the coup, raising the possibility of severe civil unrest in the coming days.

The Tatmadaw is gambling that it can weather the storm of domestic protest and international condemnation as it did when it seized power in 1988 and subsequently when it violently suppressed the pro-democracy movement in the 1990s and 2000s. That may be an overly optimistic assessment by the military. Liberalisation of the Myanmar economy in recent years has produced a high level of digital literacy among the population. Although the military will now seek to control and limit the availability of the national telecoms and Internet infrastructure, it will not be able to suppress completely pro-democracy online activism. Moreover, international condemnation of the coup has been swift, both from the EU and the US. Even the Tatmadaw’s strongest international backer, China, will not wish to see the country descend into chaos, which would threaten its significant investments in infrastructure in Myanmar.

In the short-term the coup will mean disruption for companies operating in Myanmar, and not just for companies operating in sectors dominated by holdings companies associated with the army. Telecommunications and Internet services will be suspended or will operate only sporadically for days or possibly weeks. Banks are reported to be closed which will hamper financial flows between local business units and parent companies outside Myanmar; and of course, companies will be concerned about the physical safety of their employees in-country. Myanmar is also a major producer of rare earths which are considered crucial for magnets and technology at the heart of the green energy transition. Any disruption to supplies could increase market prices globally.

Over the medium- to longer-term, the UN, ASEAN and other international bodies will consider their responses to the coup and which may include sanctions against the military regime. Certainly, countries which have long promoted democratic transformation in Myanmar will be thinking of reimposing their own unilateral sanctions which were removed progressively from 2015 when the NLD won democratic elections for the first time, transitioning away from a long period of earlier military government. It remains to be seen how these sanctions will be targeted, and how they will affect business operations generally. It also remains to be seen whether China will support multilateral sanctions, or whether it will side with its traditional client, the Tatmadaw.

Whatever the developments in the next few weeks, the coup certainly represents a severe setback to both democratisation and the continued opening-up of the economy.

By Paul Doran, Director of Investigations at Aperio Intelligence

paul.doran@aperio-intelligence.com