04/09/2019

Evaluating the impact of Michael Calvey’s arrest on the Russian business environment

2019 has all the chances of becoming one of the gloomiest years for Russia’s reputation as a country worth investing in. Over USD 40 billion were withdrawn from the country in the first half of this year, figures comparable to the height of the economic crisis in 2008 and the 2014 post-sanctions shock. This tendency, some say, is due to the recent arrests of high-profile business figures, both foreign and Russian, and the perceived lack of respect for their rights shown by Russian courts. Six well-known entrepreneurs were charged with criminal offences in the first six months of 2019, four of them arrested. The most notable, Michael Calvey, has been awaiting trial since February: first in custody and then from April, under house arrest.

This analysis considers the reasons behind the sharp increase in capital outflow from Russia, focusing on the reputational setback caused by Calvey’s arrest. A reputable American investor who made his fortune in Russia, Calvey was supposed to showcase the country to foreign businesses but he has ended up in a show trial. His partner-turned-adversary, Artem Avetisyan, is believed to have close contacts in the FSB, Russia’s security agency, which is involved in the probe into Calvey’s business transactions alongside the Investigative Committee. The growing capital outflow from Russia to its traditional recipient economies, including the UK, is not only Russia’s problem. With this in mind, Western businesses, especially banks and financial institutions, should question and examine the origins of these funds. This article also features an interview with Ilya Shumanov, the deputy head of Transparency International – Russia.

Doing business in Russia

Russia ranks 31st out of 190 in the World Bank’s Doing Business survey 20191. This is a massive improvement since 2014, when Russia came 92nd, just behind Albania and Barbados2. However, the study does not take into consideration some of the key factors for Russia’s business environment. Doing business has hardly ever been considered safe and relaxed in Russia, predominantly due to high levels of corruption and the lack of an independent judiciary. Russia has never left the bottom third of the Corruption Perceptions Index published by Transparency International. It ranked 138th out of 180 countries in 20183. According to various surveys conducted over the past decade by independent Russian sociological bureau Levada Centre, more than half of respondents in Russia do not trust Russian courts4. In 2019 Russia scored only 2 out of 16 points in an annual assessment of the country’s rule of law by Freedom House5.

Nonetheless, there used to be some arbitrary rules in place. During the rapid economic growth of the 2000s, the Russian state indirectly but clearly articulated these rules as follows: you are allowed to benefit from the country’s economic growth if you do not challenge the political status quo. According to this social contract, the state guaranteed stability for entrepreneurs in return for their political loyalty. The presidential administration appears to have also been entrusted with an arbitration role in major commercial disputes.

Following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and subsequent sanctions by the US and the EU, the Russian economy plummeted and has been struggling to recover ever since. Having failed to maintain macroeconomic stability, the Kremlin has seemingly distanced itself from mediating the commercial conflicts, while there is no independent judiciary to step in.

The complicated business environment has provoked entrepreneurs to act and, among other things, to withdraw their investments from Russia. This is accompanied by other detectable tendencies. According to the statistics released annually by London-based consultancy Portland Communications, Russians have been one of the most litigious nationalities in London’s commercial courts since 2014; in most years, second only to the British. Governed by English common law, Cyprus and the UK’s offshore territories remain among the most popular jurisdictions for holding companies for Russian businesses6,7.

Furthermore, Russian entrepreneurs are increasingly moving their assets and families abroad, including to the UK. The most recent Home Office statistics indicate that Russians have been the second largest group of applicants for the UK golden visa programme since it was established in 20088. In the 2010s, thousands of wealthy Russians were awarded golden visas in other EU member states including Cyprus, Malta, Latvia and Spain.

The current year has arguably become the most troubled time for Russian entrepreneurs in the last two decades. In addition to unpredictable prosecution (often perceived as staged by business adversaries), they have to navigate a highly corrupt environment and mind the international sanctions.

Speaking at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum on 6 June 2019, Russia’s former finance minister Alexey Kudrin stated that the capital outflow from Russia reached USD 40 billion during the first five months of 2019. He linked this to the arrest of Calvey, the largest foreign investor in Russia9.

Alexey Kudrin: Kudrin currently chairs the Accounts Chamber, a parliamentary auditor with limited public authority. He is known to have been a friend of president Putin since the early 1990s when they both worked in the St Petersburg City Administration. In the early years of his presidency, Putin entrusted Kudrin with economic reforms which proved to be highly effective. Kudrin served as the minister of finance between 2000 and 2011, and presided over Russia’s accumulation of foreign currency reserves from oil sales in the 2000s.

The Central Bank of Russia provides a more conservative assessment regarding the scale of capital outflow during the first half of 2019: USD 27.3 billion10. Nonetheless, even this figure has more than doubled compared to the same period in 2018. It is also worth mentioning that the Central Bank contradicts its own data published earlier this year, when it stated that the capital outflow between January and May 2019 reached USD 35.2 billion, a figure that corresponds with Kudrin’s assessment11.

Calvey’s arrest has indeed attracted media attention and generated uncertainty within the Russian business environment. The following section scrutinises the case as well as Calvey’s conflict with Artem Avetisyan.

Artem Avetisyan: Avetisyan is a Russian banker and public figure. He is one of the directors of the Agency for Strategic Initiatives (ASI). This not-for-profit organisation aims at improving the business environment in Russia and is chaired by president Putin. Avetisyan is also the head of Leader’s Club, which is effectively a lobby organisation for entrepreneurs. Its members have access to regular meetings with Russian public officials, including Putin and his advisors. In addition to these lobbying opportunities, Avetisyan has close relations with the sons of several senior Russian public officials. He is a business partner of Oleg Gref, the son of Sberbank’s CEO German Gref. Russian media reports that Avetisyan is a friend of Dmitry Patrushev, the son of the secretary of Russia’s Security Council and former head of the FSB Nikolay Patrushev. An influential advisor to president Putin, Andrey Belousov, has also acknowledged his friendship with Avetisyan in interviews with Russian media.

The Calvey (show)case

Michael Calvey, the managing partner of Russia’s largest private equity firm Baring Vostok Capital Investments and arguably the country’s most well-known foreign investor, was the first of a number of entrepreneurs to be charged with criminal offences in Russia in 2019. Calvey has been working in Russia since the mid-1990s. During the 2010s, Calvey famously earned 500-fold returns on his investments in Russian search engine Yandex12.

Calvey eschewed investing in state-owned enterprises. He is also known for his investments in and alongside politically exposed organisations. Since 2006, Baring Vostok has been a minority shareholder of Kaspi Bank, the largest Kazakh retail bank. Between 2015 and 2017, Kaspi Bank was co-owned by Kairat Satybaldy, the nephew of president Nursultan Nazarbayev. Despite Satybaldy’s exit from the bank’s list of shareholders, he is believed to have retained control over its management. In Russia, Baring Vostok is a longstanding investment partner of the RDIF, the Russian sovereign wealth fund. During the past three years, Baring Vostok and the RDIF co-invested in Chukotka-based coal mines, St Petersburg’s Pulkovo airport and ivi, an on-demand cinema platform13,14,15.

Calvey has a degree of political exposure in the US. His brother Kevin Calvey is a Republican politician who served in the Oklahoma House of Representatives from 1998-2006 and from 2014-2018. Michael reportedly financed his brother’s run for Congress in 201016.

Calvey retained his investments in Russia after 2014 and kept praising the country’s business environment amid the exodus of other foreign investors. Due to his reluctance to speak publicly about Russia’s evident economic problems, The Wall Street Journal dubbed him a “Kremlin cheerleader.”17 He has equally never been critical of the political regime in Russia. By doing so, he followed the aforementioned postulate of Russia’s Putin-era social contract: you can do business in Russia, as long as you do not criticise the Kremlin.

However, this pact appears to have been broken. In mid-February 2019, Calvey was supposed to meet his partner-turned-adversary Avetisyan in Moscow. Calvey and Avetisyan have been involved in a long-running commercial dispute in London over the ownership of PAO Vostochny Express Bank, a large bank based in the Russian Far East. Calvey flew to Moscow on 11 February and was detained on 15 February alongside five other managers employed by Baring Vostok. The Basnmanny Court of Moscow ordered their arrest for two months on fraud charges a day later18. Calvey was released and put under house arrest in Moscow in April, but his arrest was later extended until 13 October19,20. The other defendants remain in custody.

When asked about the court’s decision to keep the other Baring Vostok managers in detention, president Putin replied that they did not own residential property in Moscow and so could not be put under house arrest.

One of the arrestees, Phillipe Delpal, is a French national. French president Emmanuel Macron approached Putin personally regarding his detention. In July, Russian media reported that Delpal’s wife had purchased an apartment in Moscow for USD 397,00021 so that he could be placed under house arrest. The Moscow City Court agreed to move him to house arrest in August following reports that Delpal had lost 12 kilograms in weight whilst in jail22.

The Russian Investigative Committee suspects Calvey and his associates of stealing RUB 2.5 billion (USD 39 million) from Vostochny, which has been partly owned by Baring Vostok since 2010. According to Russian prosecutors, Calvey-controlled NAO First Collection Bureau (PKB) borrowed RUB 2.5 billion from Vostochny and repaid this debt in February 2017 by transferring a 60 percent stake in International Financial Technology Group S.C.A. (IFTG), a Luxembourgish investment fund, to Vostochny23. In February 2019, Vostochny’s board member Sherzod Yusupov complained to Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) that the stake in IFTG was only worth RUB 600,000 and that Calvey had defrauded his partners.

Russian news portal Open Media reviewed IFTG’s 2016 annual return and reported that the company held assets worth RUB 2.24 billion24. IFTG owned minority stakes in well-known Russian companies, including oil company RussNeft. Open Media identified no evidence of financial distress in IFTG’s financial statements.

In early August 2019, a US-registered investment fund Parus Marine sent a purchase offer to Vostochny. The fund offered RUB 2.6 billion for Vostochny’s stake in IFTG. On 9 August, Vostochny refused to sell it for the proposed price asking for RUB 3.7 billion instead25.

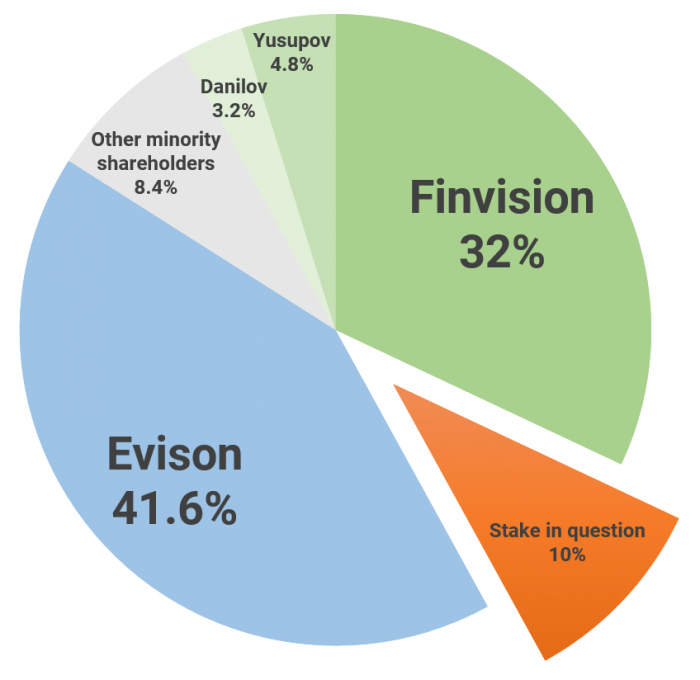

The current list of Vostochny’s shareholders traces its roots back to the bank’s merger with OOO Commercial Bank Uniastrum in January 2017. Uniastrum was a Moscow-based bank 100 percent owned by Artem Avetisyan26. Uniastrum’s assets were transferred to Vostochny as a result of the merger, while Avetisyan’s Cypriot company Finvision Holdings Limited, formerly known as Boc Russia Holdings Limited, acquired 32 percent of Vostochny. Evison Holdings Limited, a Cypriot firm co-owned by Baring Vostok and Russia Partners (which belongs to global private equity firm Siguler Guff), reduced its stake in Vostochny to 51.6 percent. Minority stakes in Vostochny belong to Avetisyan’s longstanding business partners Sherzod Yusupov (4.8 percent) and Yury Danilov (3.2 percent).

Calvey’s Baring Vostok and Avetisyan’s Finvision signed a pre-merger agreement in 2016, stipulating the latter’s right to exercise the option to increase its stake in Vostochny by 10 percent until 31 March 2018. However, Baring Vostok continuously denied Finvision’s right to buy the stake due to the alleged withdrawal of considerable sums of money from Uniastrum on the eve of its merger with Vostochny. This shareholding dispute between Avetisyan and Baring Vostok is subject to a long-running legal battle at the London Court of International Arbitration.

According to Calvey, the fraud charges against him in Russia are related to this litigation with Avetisyan in London. Calvey adds that Yusupov, who is a close associate of Avetisyan, complained to the Russian authorities on Avetisyan’s behalf in order to pressurise Baring Vostok to withdraw its lawsuit in London. In addition to the legal dispute, Avetisyan was reportedly threatened by Vostochny’s follow-on offering scheduled in April 2019. This offering was agreed in consultation with the Central Bank of Russia in January 2019 and could potentially dilute Avetisyan’s stake in Vostochny27.

Since Calvey’s arrest, Avetisyan appears to be winning the dispute over the 10 percent option. On 11 June 2019, the Arbitration Court of Amur Oblast ordered Evison to transfer a 10 percent stake in Vostochny to Finvision. The London Court of International Arbitration confirmed Avetisyan’s right to use the option on 17 June28. Evison reportedly sold the disputed stake to Finvision for RUB 750 million (USD 11.7 million) on 18 June and consequently lost majority control over Vostochny. Upon the completion of this transaction, Evison and Finvision held around 42 percent each in Vostochny29. Yusupov and Danilov, Avetisyan’s allies, also remained minority shareholders of Vostochny holding 4.8 percent and 3.2 percent of shares respectively, as of June 2019.

Therefore, Avetisyan, Yusupov and Danilov gained control over the majority of voting shares in Vostochny and called for re-election of the bank’s board members. On 28 June, the shareholders of Vostochny elected nine board members: three representatives of Finvision (Artem Avetisyan, Sherzod Yusupov, Svetlana Trukhanovich), four representatives of Evison (Grigory Zhdanov, Marina Ushakova, Yana Arutyunova, Dmitry Baburin) and two independent members (Alexander Kalinin, Yury Danilov)30. On 4 July, the board appointed Vyacheslav Arutyunyan, former senior manager of Uniastrum, as the chairman of Vostochny.

Evison challenged this appointment as well as the earlier transfer of Vostochny’s 10 percent stake in the Arbitration Court of Amur Oblast31,32. The litigation between Avetisyan and Baring Vostok in the London Court of International Arbitration is ongoing. Therefore, the related ruling regarding Avetisyan’s right to exercise the option is preliminary and might be overturned during the forthcoming hearings. Nonetheless this ruling allowed Avetisyan and his allies to gain majority shareholder votes in Vostochny. Shortly after that, Vostochny and Avetisyan’s Finvision filed two lawsuits in Blagoveshchensk33. The suits demand compensation from Evison and Baring Vostok worth RUB 22.4 billion (USD 350.9 million) in total34.

Reports by Russian business publications appear to lean towards Calvey’s opinion that Avetisyan staged his criminal prosecution. The Bell, a Russian online newspaper, quoted anonymous sources that claim that Avetisyan could have abused his connections with the Patrushev family in order to initiate Calvey’s arrest35. In addition, Avetisyan is rumoured to have been assisted by his close friend and Putin’s advisor Andrey Belousov36. In his March 2019 interview to Forbes, Belousov denied his involvement in Calvey’s arrest and laughed off the alleged involvement of the Patrushev family37.

It is worth noting that several high-profile public officials have released statements in support of Calvey. Most notably, the head of the RDIF and Putin’s close confidant Kirill Dmitriev lobbied for Calvey’s release from detention in April38. In June, Putin provided a rather reserved commentary on Calvey’s case39. He insisted on the legitimacy of prosecution, whilst noting that Calvey should be considered innocent unless the court rules otherwise.

Previously, criminal prosecution was used to pressurise Putin’s critics, which included entrepreneurs. Most notably, in 2003 Mikhail Khodorkovsky, then CEO and owner of Yukos oil company, was charged with tax fraud following his public conflict with president Putin. He was sentenced to prison in 2005 and released in 2013. However, Calvey’s case demonstrates that former rules do not apply anymore: loyalty to the regime does not guarantee the security of one’s business. The lack of clear regulations creates opportunities for those who are keen to abuse their connections in law enforcement. Calvey’s arrest has already been followed by controversial charges against five other high profile businessmen.

Other entrepreneurs are also vulnerable to such abuses and are increasingly attempting to withdraw money from Russia and reinvest elsewhere. In his aforementioned speech at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum, Kudrin called Calvey’s arrest a shock to Russia’s economy. However, with an increased influx of money from Russia, this shock is likely to echo in the Western financial environment.

This article concludes with an interview with the deputy head of Transparency International – Russia, Ilya Shumanov, about the related risks.

An interview with deputy head of Transparency International – Russia Ilya Shumanov

Where does Russian money flow when leaving the country?

The UK is one of the most popular destinations for dirty money from Russia and other Eastern European states. Lots of wealthy Russians consider the UK to be their haven of peace. They reinvest their funds and relocate their families there. They plan to spend the rest of their lives in the UK.

Before these funds can be injected into the UK financial system, they have to be laundered. Therefore, mitigation of money laundering risks should be a top priority for local businesses that wish to work with money originating from Russia. The know-your-customer (KYC) procedure and source of wealth checks help to mitigate such risks.

What risks are associated with funds of Russian origin?

These risks are well-hidden. It is uncommon these days that someone invests in the UK’s economy directly from an offshore entity which was previously involved in a bribery or money laundering scandal. The schemes in play are complex and hard to trace.

There is a straight link between corruption and money laundering. After someone steals money in Russia, where law enforcement is virtually dysfunctional, the funds need to be invested somehow. The legitimacy of such investments raise concerns. If these funds are invested abroad, they generate money laundering risks.

Financial institutions normally initiate KYC procedures when they deal with high risk individuals, for example, a politically exposed person (PEP). Yet, we know that international compliance databases are rarely up to date and do not aim to reflect the whole spectrum of a PEP’s associated persons. These databases often omit friends and acquaintances as well as the nominees who hold the bank accounts, real estate and other assets on behalf of PEPs.

The risk of political exposure is therefore the hardest to identify and resolve, in my opinion. I regularly encounter legal professionals, who are aware of the regulations, offering a full-package of services to PEPs. They make sure the funds are transferred without legal intersections with PEPs. This can only be brought to light by civil activists, investigative journalists and the respective authorities.

In addition to PEPs, there are organised criminal groups that use the same schemes and flows to launder their funds. Identification of these people is further complicated by a lack of communication between Russian and British authorities. Sometimes it takes years to share someone’s criminal record or an extract from a court case.

What sectors of the UK’s economy are exposed to such risks?

Firstly, the British banking sector which is closely connected to European member states and has good links with the Baltic States. Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Moldova and Cyprus, which serve as traditional “buffer states” between Russian money and the UK’s financial system, used to be rather reluctant to scrutinise the source of funds. Consequently, Russian money easily accessed the UK through these economies.

Investment funds generate a further risk. They work with clients worldwide and are quite open-minded regarding funds of questionable origin. If the money does not come from Russia directly but, for example, through Cyprus, it will be more than welcome. After a while, such investments are returned and become legitimate profits.

Thirdly, migration intermediaries are exposed. The UK’s Tier 1 investor visa programme has already attracted many Russians. Some of them have already managed to become UK citizens. I have not seen any significant revisions to this programme, therefore, large amounts of Russian money of questionable origin remains in the UK economy.

Substantial funds are being laundered via the UK’s real estate market. Properties are often purchased using offshore legal entities whose ultimate beneficial owners are not disclosed. Not even to the UK authorities.

The UK’s market for luxury commodities is at risk. It is rare that source of wealth is verified before the purchase of luxury cars or jewellery. The same is true for some other niche markets, including art or horse trading. These markets are under-regulated and we have revealed some instances of their abuse.

Cryptocurrency is another unregulated market. Young crypto investors from Russia and other former Soviet Union states have literally occupied the UK’s financial sector. In reality, these people often act on behalf of someone else, who later buys a stake in a crypto company during its ICO. They launder money via such transactions. Compared to the US, where a separate FBI unit investigates cryptocurrency-related crimes, Russian law enforcement only probes a case or two.

What are the potential sources of such wealth?

According to Igor Artemyev, the head of Russia’s Federal Antimonopoly Service, the Russian economy is dominated by state-owned enterprises and businesses that rely on public procurement. This situation is only worsening year by year.

Russia’s economics work this way: a company needs cash at some point; it sets up a shell company and transfers cash through it. Cashing in is, in fact, money laundering. Despite being a criminal offence, this is common practice because Russian companies cannot survive without cash. Therefore, we should consider that money of Russian origin is highly likely to be earned via illicit transactions.

How effective are current UK regulations and law enforcement in combating dirty money from Russia?

Unexplained wealth orders (UWOs) are the regulatory tool designed to identify money of questionable origin. If this tool had been applied effectively, it would have decreased the number of those who wish to invest dirty money in the UK. This public image and reputation would be enough to stop the attempts to launder money through the UK’s financial system.

However, I do not see a persistent will to apply UWOs. Law enforcement efforts are also likely to be hindered by Brexit. As an attempt to create a sovereign system, Brexit will definitely affect the cooperation between the EU and British law enforcement and generate mutual distrust. The UK has pioneered anti-corruption and anti-money laundering initiatives. Brexit will probably limit both its resources and cooperation with foreign partners.

Dmitri Gorelov

Analyst, Russia, CEE & Central Asia

Aperio Intelligence

dmitri.gorelov@aperio-intelligence.com

- Doing Business 2019, The World Bank, accessed 7 August 2019.

- Doing Business 2014, The World Bank, accessed 7 August 2019.

- Corruption Perceptions Index 2018, Transparency International, 29 January 2019.

- Институциональное доверие, Levada Centre, 4 October 2018.

- Freedom in the World 2019, Freedom House, accessed 8 August 2019.

- Insight: Bank documents portray Cyprus as Russia’s favorite haven, Reuters, 15 May 2013.

- Российские инвесторы ушли с Кипра на Виргинские острова, RBK, 13 September 2018.

- How $220 Billion Of Dirty Money Is Laundered Through Europe, Forbes, 24 July 2019.

- Кудрин: арест Калви повлек удвоение оттока капитала из России, TASS, 6 June 2019.

- Отток капитала из России вырос более чем в два раза, Kommersant, 9 July 2019.

- В ЦБ сообщили, что чистый отток капитала из России за пять месяцев вырос до $35,2 млрд, TASS, 11 June 2019.

- Baring Vostok Backs Amazon Clone After 500-Fold Yandex Win, Bloomberg, 30 April 2013.

- РФПИ даст стране угля с Чукотки, Kommersant, 13 December 2013.

- РФПИ и арабские инвесторы закрыли сделку по покупке 25% Пулково, RBK, 4 September 2017.

- Консорциум РФПИ и Mubadala при участии Baring Vostok инвестируют в онлайн-кинотеатр ivi, Interfax, 6 June 2019.

- Oklahoma elections: Russian fund boosts Calvey campaign, The Oklahoman, 8 August 2010.

- ‘Last Man Standing’: An American Investor in Russia Takes a Fall, The Wall Street Journal, 31 July 2019.

- Суд арестовал фигуранта дела Baring Vostok Майкла Калви, RBK, 16 February 2019.

- Майкла Калви перевели под домашний арест, Kommersant, 11 April 2019.

- В деле Майкла Калви не хватает экспертиз, Kommersant, 9 July 2019.

- Putin Told a Jailed French Banker to Buy a Home. It Didn’t Help, Bloomberg, 23 July 2019.

- Фигуранта “дела Калви” Филиппа Дельпаля перевели под домашний арест, Interfax, 15 August 2019.

- Почему задержали основателя инвесткомпании Baring Vostok, RBK, 16 February 2019.

- Что не так в расследовании против Майкла Калви, Open Media, 15 February 2019.

- «Восточный» отказался продавать акции из дела Калви за 2,6 млрд руб., RBK, 9 August 2019.

- «Эти ребята прекрасно знают, как тут все устроено»: против инвестбанкиров из фонда Baring Vostok использовали серьезный ресурс, The Bell, 16 February 2019.

- «Восточный» резерв, Kommersant, 16 January 2019.

- Arrested in Russia, U.S. Investor Faces Setback in London Court, Bloomberg, 18 June 2019.

- Baring Vostok передал 10% “Восточного” компании Аветисяна и утратил контроль над банком, Interfax, 18 June 2019.

- Акционеры банка «Восточный» сформировали совет директоров, Kommersant, 28 June 2019.

- Baring Vostok оспорил потерю контроля над банком “Восточный”, Interfax, 24 June 2019.

- Смену руководства банка “Восточный” оспорили в суде, Interfax, 5 July 2019.

- А04-5290/2019, Kad.Arbitr.ru, accessed 8 August 2019.

- Компания Аветисяна предъявила претензии Baring Vostok на 12,5 млрд руб., RBK, 2 August 2019.

- «Эти ребята прекрасно знают, как тут все устроено»: против инвестбанкиров из фонда Baring Vostok использовали серьезный ресурс, The Bell, 16 February 2019.

- Основателю фонда Baring Vostok дорого обойдется конфликт в банке «Восточный», Vedomosti, 17 February 2019.

- «Если бы я пошел к президенту, меня бы вынесли вперед ногами»: Андрей Белоусов о деле Baring Vostok, Forbes, 20 March 2019.

- Глава РФПИ повторно ходатайствовал о смягчении меры пресечения Калви, Interfax, 9 April 2019.

- Путин впервые публично прокомментировал арест Калви, BBC, 7 June 2019.